I’m still feeling my way with this Substack business. So far you’ve had posts on history and tango and general waffle about writing. The history seemed popular and it is what I do, so I thought I’d try that again. This week I’m following up the post on Napoleon on Elba with a piece about his getting off the island.

I’m also giving you the opportunity to vote for whether or not you want more of this sort of thing, a short note on a funny thing Georgians did with their furniture, and a random picture of something beautiful I came across this week. Enjoy what you want, ignore the rest, and do please tell me which bits were which.

AND WITH ONE BOUND, HE WAS FREE

A couple of weeks ago, I posted here about Napoleon’s time on Elba. From the point of view of the rest of the world, the most important thing about Napoleon and Elba was his leaving of it.How did it happen? How did Napoleon escape from Elba?

In my previous post, we saw that he was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with life there. He could probably have coped with the boredom – he had always been fascinated by detail and immersed himself in the various projects he had set up on the island – but he was not prepared to tolerate the French reneging on their promise to pay him a pension or the attempts to keep him from his son. He knew that he still had supporters in the army and in Paris and he decided it was time to leave Elba and join them.

Although the British kept a representative, Sir Neil Campbell, on the island to keep a discreet eye on Napoleon’s activities, the Emperor was quietly able to buy military supplies. He had these put aboard the ships of his little navy (generally used to bring supplies to the island or to move him to the adjacent islands of the archipelago of which Elba is a part). The horses of his Polish Lancers were prepared for immediate movement and the saddlers were kept busy ensuring that all their harness was in good order. The troops were inspected and new NCOs were appointed.

It’s remarkable that, given all these clear military preparations, the secret of Napoleon’s planned escape seems to have been well kept. The only person who knew for sure was Princess Pauline, who wormed the secret out of General Bertrand, one of the two men Napoleon had entrusted with his plans. She had her silver shipped to Livorno in Italy for safe-keeping a few days before the escape, but even then no one seems to have appreciated the significance of this.

Neil Campbell was so blissfully unaware that there might be anything amiss that on 16 February he left Elba to visit the Italian mainland. Such visits were a frequent occurrence, ostensibly to liaise with officers in Italy, but in fact to visit his mistress, Countess Miniacci, in Florence. (There are even suggestions that she was a Napoleonic agent.)

Campbell’s own account of his unfortunate decision to leave the island appears in his published journal:

On February 16, I quitted Elba in HMS “Partridge”… upon a short excursion to the Continent for my health… I was anxious also to consult some medical man at Florence on account of the increasing deafness, supposed to arise from my wounds with which I have been lately affected.

Campbell’s position was made worse when his captain let fall to the French that the Partridge was to return to the mainland to pick him up ten days later. Napoleon thus knew he had ten clear days to make his preparations and escape before Campbell or the Partridge were in a position to stop him.

With Campbell away, Napoleon was able to order that no ships were to sail from Elba, so that, even if there were suspicions about his plans on the island, there was no way to get news to possible enemies.

As part of the pretence that all was normal, on 25th of February Napoleon and his officers all attended a ball given by Princess Pauline, but the next day at about one o’clock in the afternoon the gates of the town were closed and Napoleon’s army received its orders for departure. Even at this stage nobody was told where they were going. If the British had had an inkling of Napoleon’s plans to escape, they would almost certainly have assumed that he was heading for Italy. There were even suggestions that Elba had been chosen for his exile in part because it suited the Russians to have the Austrians permanently needing to keep up their guard up against potential Napoleonic interference with their Italian possessions.

By mid-afternoon, Napoleon’s fleet was ready to sail. At eight o’clock Napoleon himself boarded his brig, the Inconstant. Extra cannon had been mounted aboard and her hull had been painted in the colours usually used by British ships, to improve her chances of escaping any blockade. She was accompanied by the Stella, the other ship of Napoleon’s navy, the Caroline, a French merchant brig, the St Esprit, which had been chartered for the occasion and three other small vessels. He probably had around a thousand men with him.

When the fleet left Elba, it was carried by a good southerly wind, but the next day the wind dropped. It must have been a nerve wracking time for Napoleon. The Mediterranean was patrolled by French and English fleets and every British ship had a portrait of Napoleon in the captain’s cabin, so that he could be easily identified if intercepted on the high seas. The calm did affect the enemy as well as him, though. Because of the lack of wind Campbell did not arrive back on Elba until the 28th, so the alarm was not raised until two days after Napoleon’s escape.

The winds picked up again on the 27th, but the Inconstant was hailed by a French naval ship, the Zephyr. Its master, realising that the Inconstant had sailed from Elba, asked how Napoleon was. “Marvellously well,” came the reply – supposedly dictated by the Emperor himself. With no reason for suspicion, the Zephyr allowed Napoleon’s vessel to pass.

Napoleon landed in France near Antibes on March 1, 1815. He had, as the Bonapartists had always believed, returned as the violets bloomed in the spring. The events that led to Waterloo were under way.

FURTHER READING

Peter Hicks (2014). Napoleon On Elba – An Exile Of Consent. Napoleonica. La Revue, 19,(1), 53-67. doi:10.3917/napo.141.0053.

Katherine Macdonogh (1994) ‘A sympathetic ear: Napoleon, Elba and the British’ History Today, vol. 44

Campbell’s journal was published by his nephew under the title Napoleon at Fontainebleau and Elba (John Murray 1869)

For a detailed account of Napoleon’s time on Elba and his escape, see The Island Empire by the anonymous ‘author of Blondelle’, published by T Bosworth in 1855 and available in Google Books.

A WORD FROM OUR SPONSOR

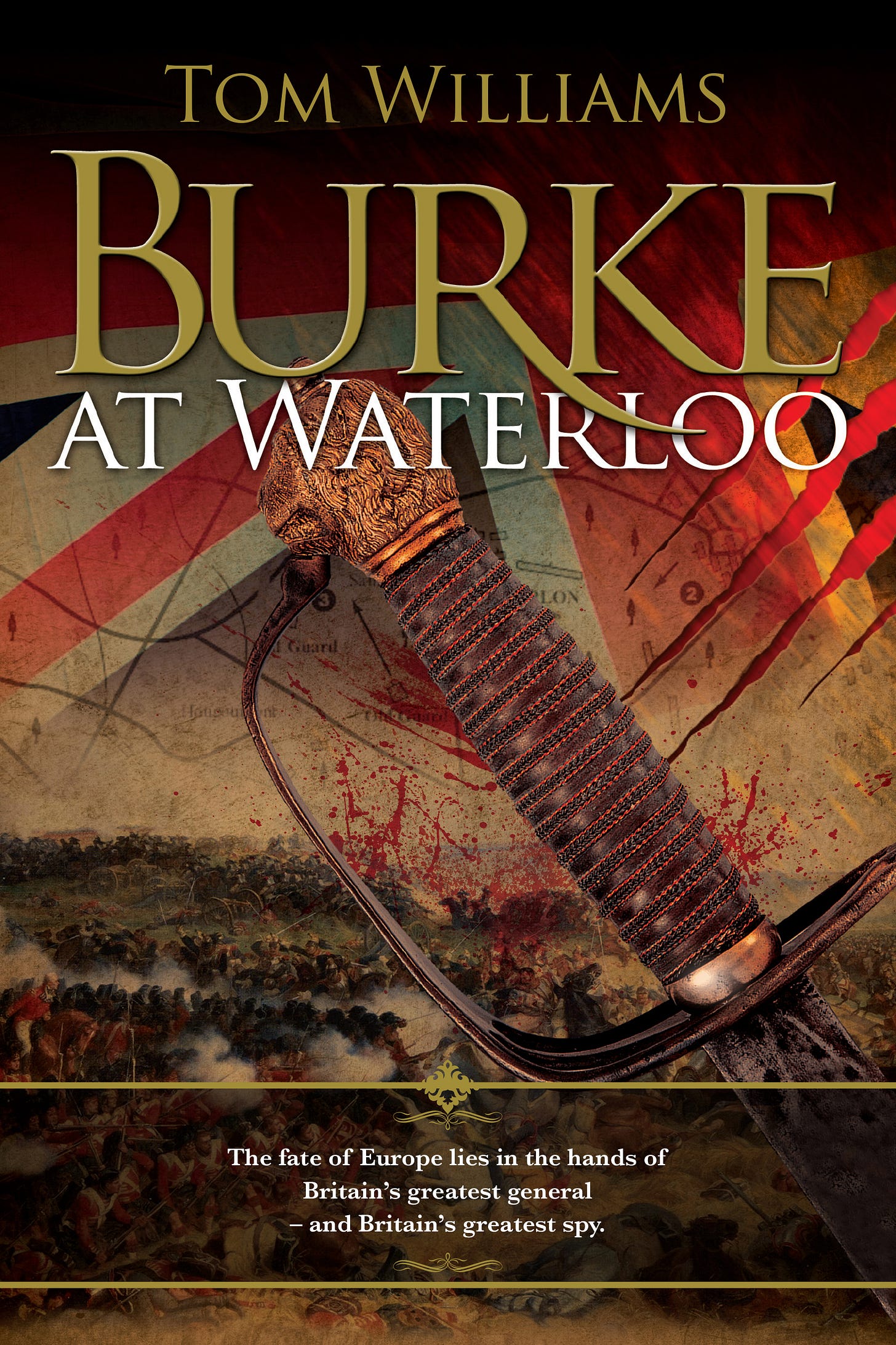

Burke at Waterloo was the third of my Burke books. Back then, I didn’t self-publish and my then publishers were very keen that I have Burke at Waterloo for the 200th anniversary of the battle. (Yes, I have been writing Burke books for a long time.)

The James Burke stories are not military history like (an obvious comparison) Cornwell’s ‘Sharpe’ books. Burke is first and foremost a spy, but he’s a soldier too, so there are battle scenes as well as adventures that owe more to James Bond than Richard Sharpe. Burke at Waterloo combines both Bond and Sharpe. It starts with Napoleon safely on Elba, while Burke is in France to track down Bonapartists who are plotting for the Emperor’s return. Suddenly his counter-intelligence work is interrupted by Napoleon’s return to France. His pursuit of Napoleon’s spies has taken him to Brussels and the climax of his chase is on the field of battle at Waterloo. It’s a thrilling read and a painless way to learn more about that famous battle. Do give it a go.

HOW MUCH HISTORY IS TOO MUCH?

I mentioned above that I have a whole series of posts (no longer available on my blog) which are effectively a draft for a history of the events that led up to Waterloo and the battle itself. I have argued in the past that the battle of Waterloo had a historical impact that still underpins much of the way the British see their place in the world today and, like many people, I’m fascinated by the history that led to the battle and the way it has been interpreted since.

Given the importance of the battle it is surprising how much ignorance there is about it from all but those enthusiasts who can, moving to the other extreme, tell you the exact position of every unit throughout the fighting.

My writing about Waterloo tried to come between these two extremes, but in the end I was not sure that there was enough interest to justify trying to turn it into something for wider publication. Perhaps I'm wrong. Substack seems to give me the opportunity to try out an early version and get feedback, but do people really want to read this?

One possibility will be that I make the Waterloo posts available on paid subscription for people who would be interested in them and make the free posts less (in comparison) historically heavyweight? I’d love to hear your views, so do please comment but, knowing that people are often slow to write in, I’m going to try a very simple poll first. Do you welcome history pieces like the ones on Elba, or would you rather read other stuff? I’ll run this for a week and think about where to go next

INTERIOR DECORATING GEORGIAN STYLE

I spend a lot of time at Marble Hill House, where I volunteer for English Heritage. Naturally enough, I’ve begun to get quite interested in how the Georgians decorated their homes.

Henrietta Howard, who had the house built, had this pier table made for the place.

It’s a lovely piece and made with the pattern along the base matching the pattern on the skirting board behind it. The base has even been cut to fit flush with the skirting board as well as the wall behind it. (Do ask if you want more detailed photographs.) The question is, why has English Heritage had to put the table on a small raised plinth? It’s the original floor and the original skirting board, so given the care that has gone into making the table an exact fit with the room, why does the base seem an inch or so too low?

I have no idea, but I’d assumed it was because of damage of some sort in the almost 200 years that the table was removed from the house. Then I visited Houghton Hall in Norfolk, a rather more splendid house built for Sir Robert Walpole at about the same time as Marble Hill. There I saw that furniture had been balanced on little stones, even when it didn’t have to line up with anything.

I still have no idea why this was done, but it seems to have been a regular feature of interior decoration 300 years ago and something you won’t see if you look at furniture out of context. I’d be fascinated if anyone can throw some light on why this was done.

AND FINALLY…

I live quite close to Richmond Park and, over the years, I have taken far too many photos of deer there. I keep promising myself that I won’t take any more but, as we approach the rutting season, this splendid stag was too beautiful to resist.

I love that his ship was called Inconstant….

You’ve just reminded me that my favourite childhood author, Geoffrey Trease, wrote a book called “Violet for Bonaparte”. Most of my knowledge of post-Reformation history comes from Trease, as I was made to give up history at school at the age of thirteen.